|

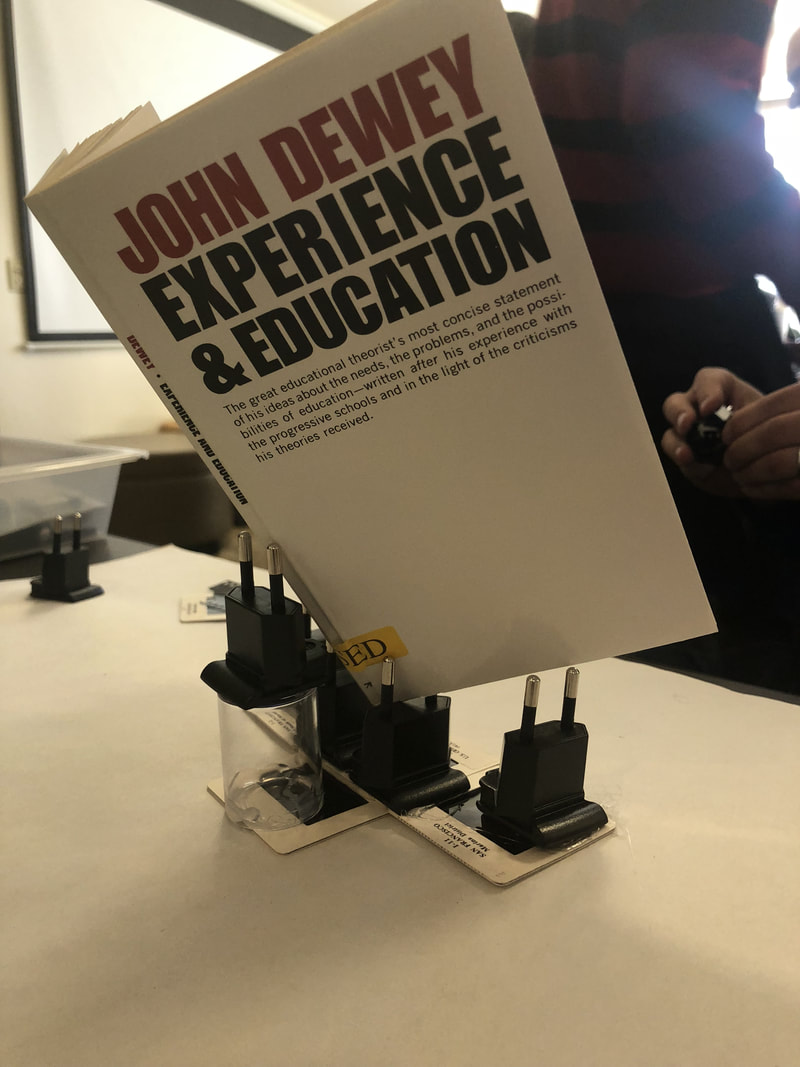

We are two weeks in and today's face-to-face lab challenge was an upcycling, unconventional materials challenge. We gave students CDs, international adapter plugs (salvaged from the Galileo boards Intel donated), plastic caps, etc. We first asked them to explore the materials, then to make something from them. There were several very nice creations, but one of our favorite creations, in part because of the book the student brought was a book holder: Up next week: LEGOs + LEDs!

0 Comments

Last night, I found out my NSF CAREER proposal has been awarded. So it's time to update this space, because this is the space that led me to the idea of framing agency. Messing about with stuff and making sense of that mess got me thinking about the kinds of decisions we make in design, and how some decisions consequentially maintain the design space, and others shut it down. In this project, I am investigating how these decisions relate to agency, identity and learning.

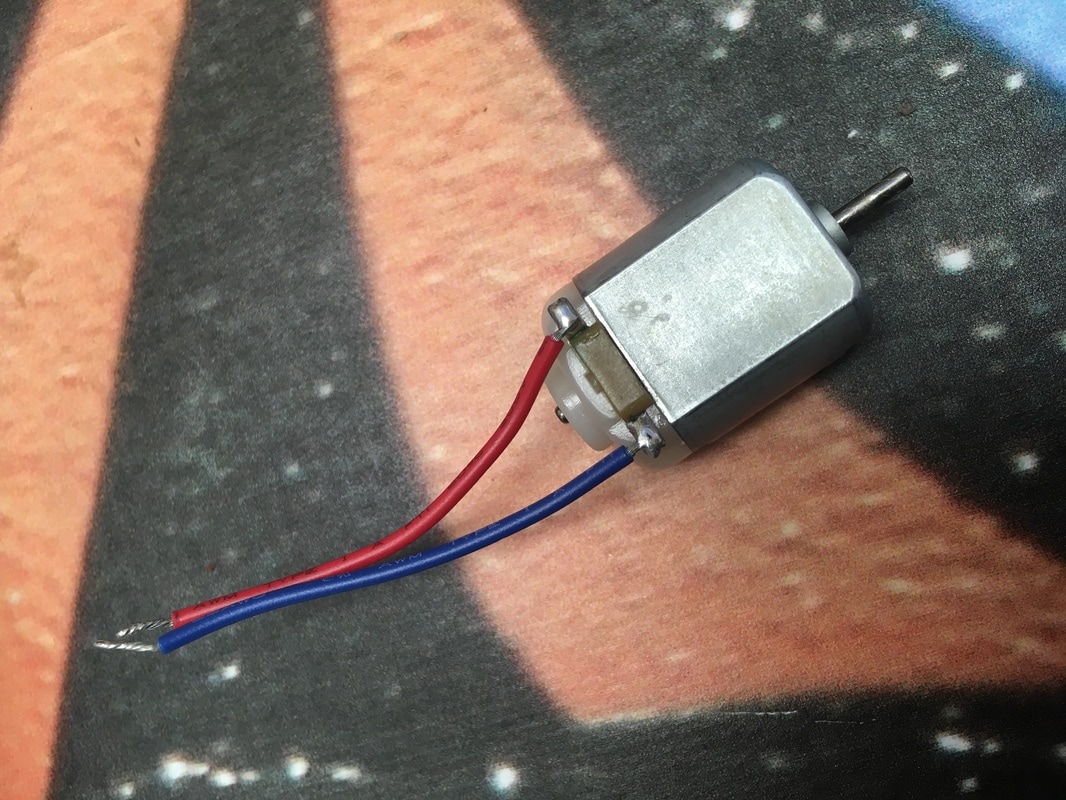

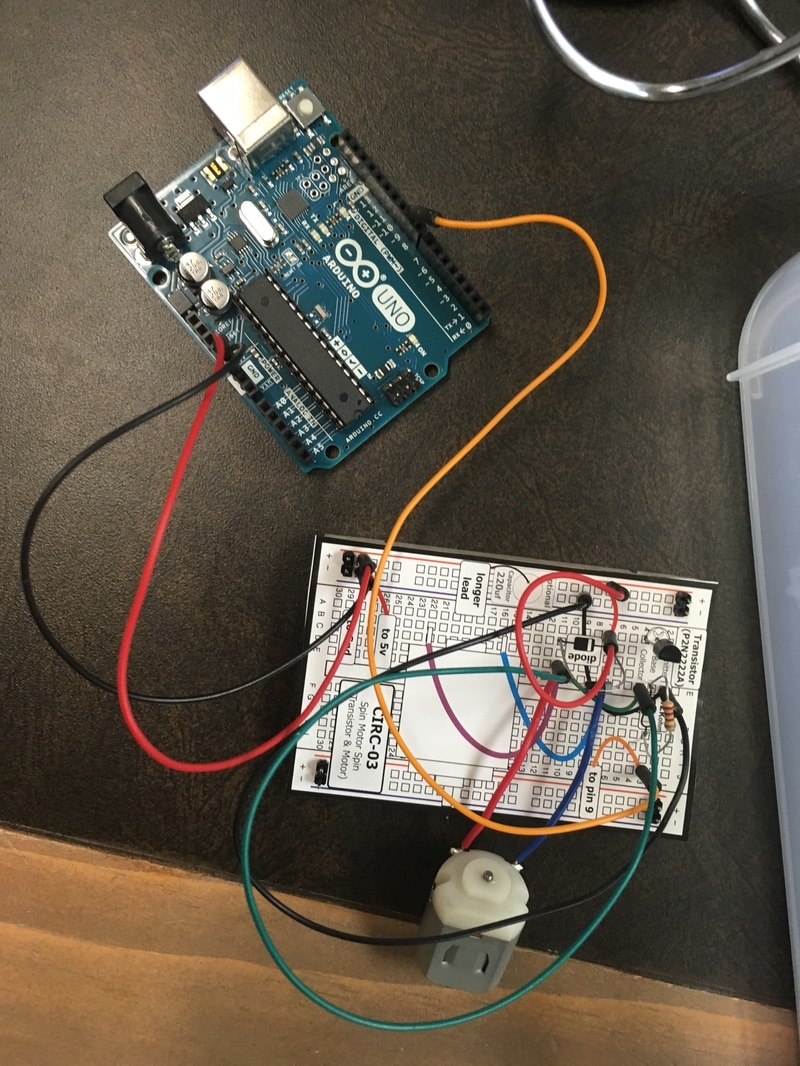

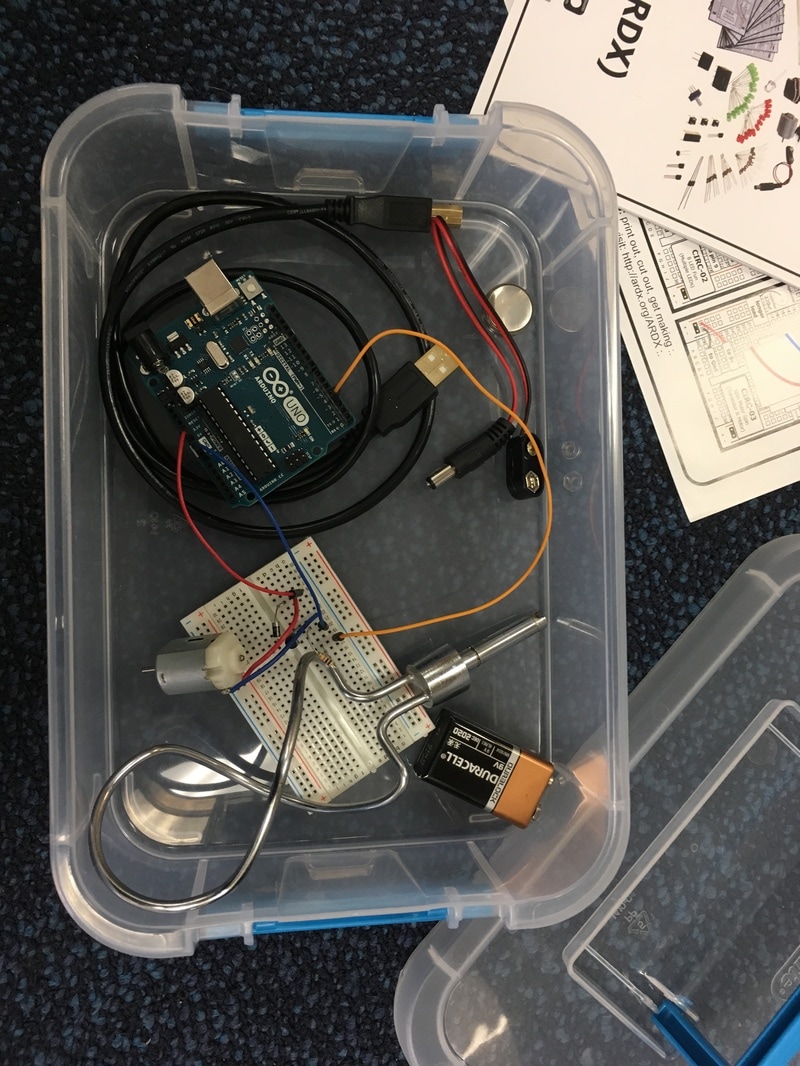

I have set up a sister blog to focus just on that work. I had a few goals, based on the questions I posed in a recent blogpost. I wanted to find a way to power my PKE meter, I wanted to turn a beater from an old stand mixer into the pink part and add a blue LED to it, I wanted to move off my breadboard, I wanted to create a housing, and add a switch. Powering it turned out to be easy. I did some googling and found that while a 9-volt source is nto efficient, it will work. I knew I had a 9-volt battery adapter in my boxes of stuff. When I plugged in the external power source, the motor started right up, which is when I realized that the code was still on my Arduino. Yay! So then I set about trying to attach the mixer, and immediately ran into a problem: the beater was WAY too heavy for my little toy motor! At first I wondered if there was some way to get around that issue. Then, instead of facing it, I started working on the other issue: my toy motor had a smooth shaft. This itself presented two problems. First, I couldn't figure out how to attach anything to this surface, given the amount of spinning it is supposed to do. Second, I found myself reluctant to mention to the others in the room (read: men) that I didn't know how to stick anything onto the "smooth shaft" on my motor. And don't get me wrong—these were wonderful, supportive men. But in anticipation of either snickering or the fear that it would sound sexual/flirtatious, I said, "The motor thingy is smooth and I can't get stuff to stick to it. Do you have any ideas?" making me sound inept, but not sexual. This really makes me wonder how much language like this holds women back.  Once you get your motor spinning, take care when placing other objects onto its smooth shaft. I tried a number of ways to make attachments, and the most promising materials turned out to be the low fidelity stuff: craft sticks and super wikki stix. If you have never used wikki stix, think yarn-dipped-in-wax. They are posable, sticky, colorful, and cut-able. Pretty useful low-fi prototyping material. I also toyed with copper tape and blue LEDs. I ended up making three basic versions quickly, and did a bad job of documenting. The first was a compromise between the original and 2016 Ghostbusters version of the PKE meter: two craft sticks in a V shape, with LEDs at the end, and wrapped with a pink wikki stix to hold it together, and with some slightly complicated arrangements to create a parallel circuit with one battery. This looked pretty cool, but splayed when the motor began spinning. I quickly discovered that any version not connected at the top would do this, because physics works. I also realized I would also need a way to switch the battery on and off, and the copper tape is too fragile. Chris suggested using a wire, and this gave me the idea of adding pipe cleaners to my design. I moved to an all-wikki stix version, but realized right away this was too floppy. I then recalled (precedent!) that pipe cleaners are conductive. I snipped one into two pieces, stripped the fuzz off the ends, then used the wiki stixx to get everything into place, including a coin cell battery. This still seemed floppy, so I added a central craft stick. This was promising, but clearly still too heavy. I decided to start over with a lighter design, and repurposed one of the copper-tape lined craft sticks from my first prototype. This worked better, with the motor shaft stuck into a waxy ball made out of wikki stix (again with the temptation to call it a motor thingy). The smooth shaft was still an issue. I kept the design, but dug through my boxes of stuff to find another motor, and managed to find one with an attached gear. My other goal was to try to get my design off the breadboard. I talked to a computer scientist earlier in the day who seemed skeptical about my plan to use a piece of plastic and copper tape. Maybe reading this, you are skeptical as well? I looked up a schematic for how breadboards work, and set about reproducing the connections I needed, then began building a new prototype on this, that I thought matched my breadboard design. I transferred over my new motor to my copper tape version, and then plugged into my Arduino board. Success! In reflecting on my process, I realize I almost deliberately set myself up for failure with the copper tape prototype. I was pretty sure it would not work, and figured that failure would force me to learn why it failed. It didn't fail, and I am not sure I learned much, but I did notice much more about what is connected to what, and this is making me a bit curious about the various things that are a part of this design. Now that the breadbox is gone, some of the black box feel is gone. I can see what is connected to what. But I wonder if there is a better design for a teaching breadboard, that more clearly illustrates where the connections are?

I also note that I felt pretty sad when my beater turned out to be too heavy. Others had predicted it, but not connected its heaviness to the motor. At first, the beater seemed like such a fun choice. I was a little uncertain about how to put an LED on it, because I figured it would be conductive, but I had too little experience to predict that the heaviness would be an issue. This realization made me reframe the design. As I worked with the parts, I thought about their fragility, their temporary-ness on the breadboard. Because I am working in territory that is new to me, with materials that are unfamiliar, I find that I am not able to predict well what will work and what won't work. Each success brings a new horizon of problems and possibilities. What does it mean to make something abstract or conceptual? A number of years ago, someone posed a question about having an abstract experience. In response, I sewed a Möbius strip. Although I knew I would only need to sew one side, when my presser foot ran over the already-stitched down edge, it completely violated my expectations. I made four more, and each time, felt a little frisson of delight as my presser foot approached the stitching. As if it would be different on the third or fourth try. I don't think I learned anything new in doing so, but it was a memorable experience. Building on that, as I am working on projects, I am also trying to make progress on constructs. As a constructionist, this is pretty normal for me. So, what have I been making and making progress on lately? My first Arduino project! I am trying to make a PKE meter. My first attempt at getting my motor to spin was a fail. I had zero idea what went wrong. A friend gave me advice:

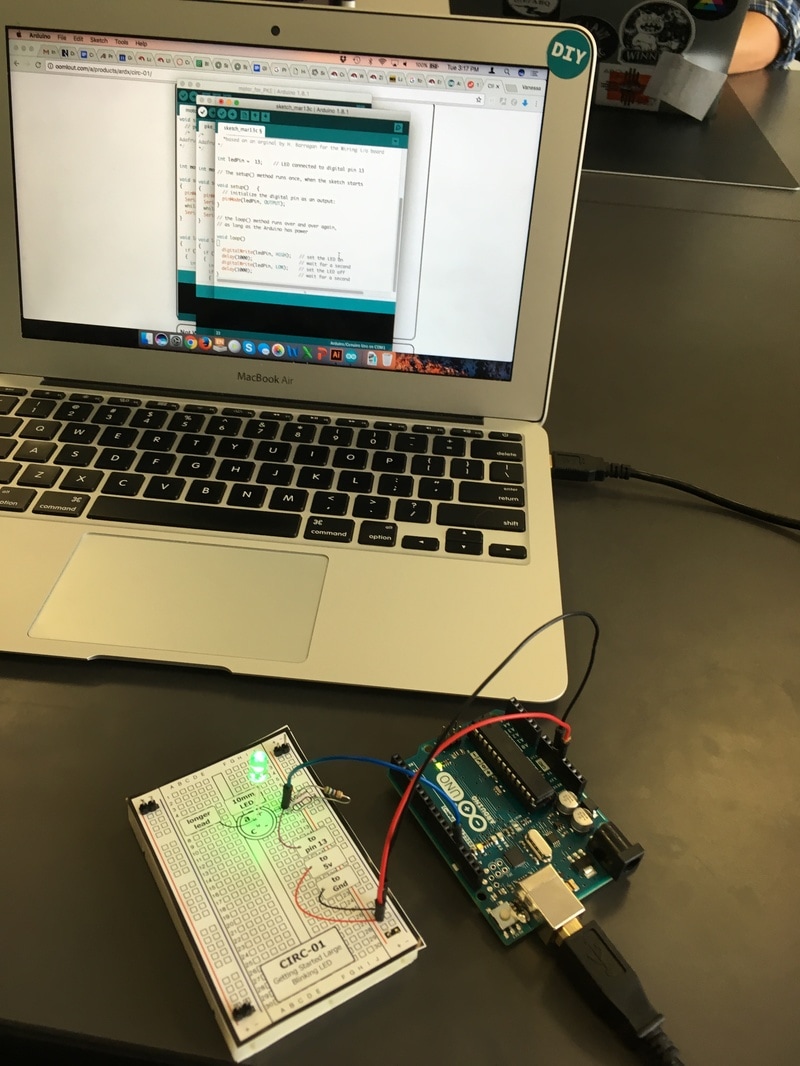

And then Chris asked me something about how or why it worked. Well, THAT metaphorical lightbulb did not go on. I have no idea why it worked, or how it worked. Meaning I made progress on my device, and maybe developed a little self-efficacy for following Arduino directions, but not much else. Still, I plunged ahead, and found directions for making a motor spin. I followed them. And now I have a motor that spins! But still no understanding. However, I do now have lots of ideas. And lots of questions.

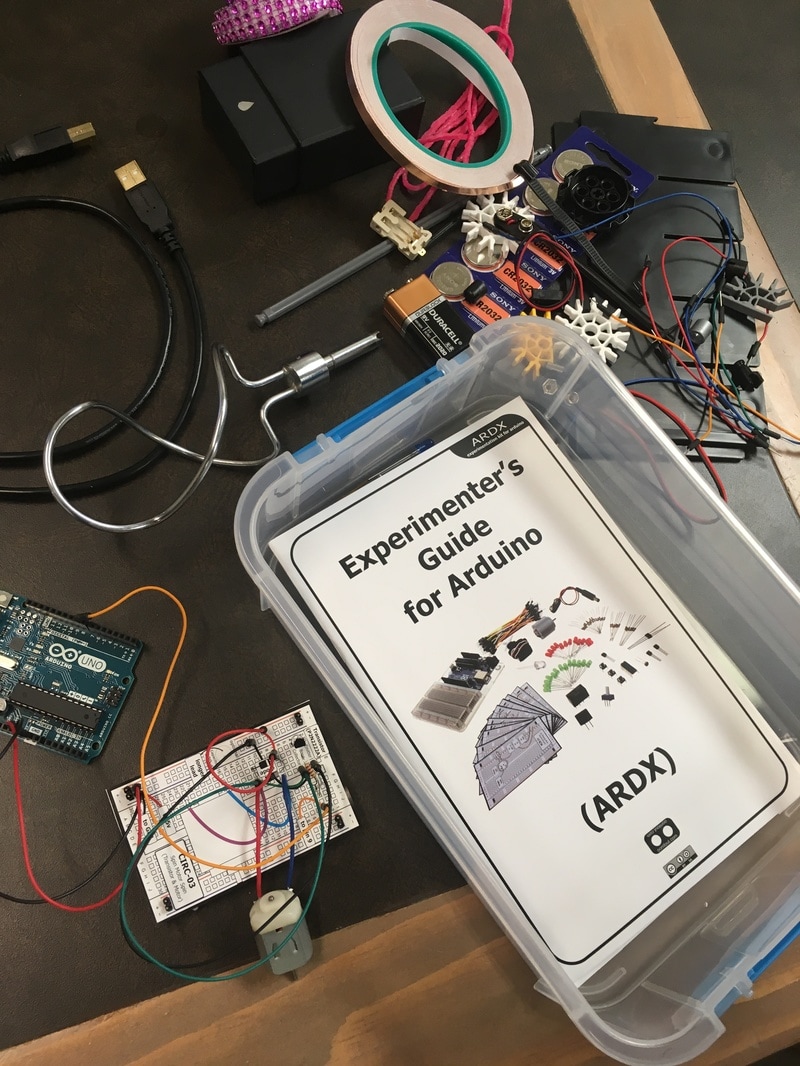

All of these questions show progress on my framing of the problem. I am getting further into the problem. And starting to see the affordances and constraints of my approach. So I went and dug through the random stuff in the lab, and this is what I have to work with now: So, how is this helping me make progress on the construct of framing agency?

A friend offered to just make this thing for me. I said 'Great, but I am still going to try to make one myself.' Others have offered to sit with me and walk me through this. And so far I have turned them down. Part of that is because I want to do this myself. I want to be able to frame and reframe as I go. But if I am honest, part is because I think it will be clear just how little I know about coding and electronics. I am not worried about that, but rather what might happen as a result. Someone might feel the need to explain it all to me. And right now I am chasing a goal, and learning just the bits I need to to make progress. I think people probably do this quite a bit. I don't want it to become schoolish. I want to puzzle and tinker my way to making what I want to make. This type of need-to-know is found repeatedly when we try to insert learning into making. This reminds me of the work by Leona & Rich on students' use of engineering versus scientific models of experimentation, and how there might be a somewhat natural progression from engineering to scientific approaches. As a former geologist and current learnign scientist, I do know the scientific model of experimentation. But as a designer, I favor the engineering model, tinkering my way to making it work. I feel more sense of framing agency. Maybe there will come a point where I reframe my goal to be able learning how my PKE meter works. Though I suspect any such framing will be driven only by it not working. So, what am I making progress on? NOT on programming or circuits. But I am understanding better why attempting to insert learning goals into making goals might fail! Imagine you have a brick, a string, a paperclip, and chewing gum. Come up with as many possible uses of them as you can.

Does doing problems like this make you more creative? While you can get better at tasks like this—tasks that are context light or context free—such tasks don't appear (from the research literature) to enhance creative capacity in disciplinary/domain-specific settings. Creativity seems to be discipline-specific. And this makes sense. Many people feel their creativity is welcomed in certain places (creative writing, art class) and unwelcome in others (math class?). But this also varies across people, mostly based on the experiences they have had. Some people feel very creative in mathematics yet feel rigid and constrained in prototypically creative spaces. So one of the things we are exploring is how to reframe this problem. If giving people creativity tasks is not the answer, perhaps the problem is not with the tasks themselves, as much as the instructional design surrounding the tasks. Or perhaps we need a continuum of tasks, stepping people from tasks that invite their creativity to those that repel it. I suspect we need some practices as well, some scaffolds to fade. So the questions I have are: How might we design learning experiences so that learners get more reflective/metacognitive about the strategies they use to be (un)successfully creative, and the conditions that (dis)invite their creativity? How can we foster a willingness to approach problems/situations as malleable/reframable? What practices/tools could help in this endeavor? I think the construct I want to develop is framing agency—that is, the ability to take ownership of problems/situations and shape them, flip them, find their tractable parts, their movable parts, and rework them into something better. Framing agency is something I have and use daily. Having spent some time in situations where I wasn't comfortable being my weird, creative, nerdy, playful self, I am keenly aware how context-dependent agency is. Having suppressed that part of myself for the better part of 5 years, and then having come back to myself, I feel like I have good grounds for comparison. I am happier and do more interesting, more fulfilling work when I have it. I named this blog 'making space,' which was a rapidly-made decision that turned out to be productive. It felt like it fit at the time. But I didn't know why. Most spaces where people make things are called "maker spaces" (or fablabs). And that says that you have an identity as a maker. I don't always feel like a maker, and maybe you don't always feel like a maker, but that doesn't stop us from making things. And we are also making the space into something new. When giving a tour of the space the other day, someone commented on our column, which began as an eyesore—a bug—that we have now transformed into the coolest part of the space—a feature. So it is a space for making and a space we are making. As a constructionist, (this stance is tied to why I decided to blog about all this, to position it as public), I also see it as a space for making ideas, constructs, studies, etc. Which makes me ponder, in this exploratory time, what are we making progress on? In reflecting on this with Richard Reeve, I found something exciting in the making: We are developing a practice—not yet formalized—that could be very helpful for eliciting problem framing. One of the big challenges in studying problem framing is deciding what is sufficient evidence, in terms of whether framing is happening, what the frame is, and when it has changed. Something I have noticed in my own exploratory work is that I began using a sort of think aloud protocol to narrate my work. In doing so, I realized I was making clear my long term problem goals (the larger problem frame), as well as the short term and emergent goals. I have been trying to turn a beater from a stand mixer into PKE meter. And I know I need to learn some programming and some electronics, both of which are (mostly) new to me. A future PKE meter! So this tells me I can attend to two frames at once, and I don't think we talk much about this in the study of problem framing. But it also means we have a practice we can build into our studies, a practice we can scaffold with technology, or with instruction. It is not exactly goal-setting, though it resembles it. (And Michelle Jordan's work on managing uncertainty seems pretty relevant here). It is attending to—and giving voice to—these emergently, in conversation with materials, as reflective practice. Of course, there are many literatures to build on here: metacognition, self & co-regulation, probably others... But so much of those have focused on well-structured problem solving, that I don't know how well they fit, whole-cloth. What I am after here is enhancing peoples' capacities to take ownership of problems, to frame and reframe them, to learn with excitement, and to forge ahead in the face of uncertainty by using resources, tinkering, and generally failing a lot. Using resources and tinkering, right before failing a lot!

One of the things I want to do is avoid what I (provocatively) refer to as "sweatshop theory." I don't think it serves us well to do work that is not accessible to people, but is built on the backs of people. In chatting with my colleague, he mentioned that he writes for reviewers. That seems like a very prudent strategy. But it is not mine. I realized I write for my participants. When I write, I imagine them reading it. This is probably common for those who have done lots of participant observation and member checking, but I don't think I had articulated it until recently. And so, in this vein, I want to start building a lab lexicon that makes the terms I am exploring accessible. Here is a start: materiality how the materials “talk back” to you as you work with them. What do these puffballs tell you to do? (re)framing

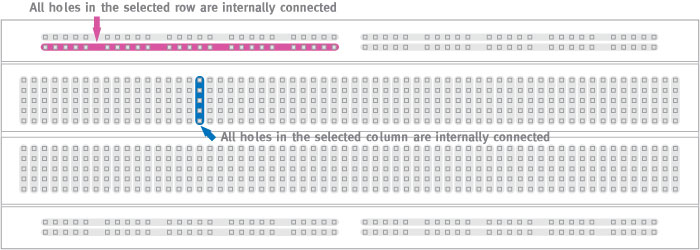

how you decide what parts of a problem matter and what parts you will work on. fixation getting stuck on an idea or an assumption about how something “ought to be.” co-regulate how you plan, monitor, and evaluate everyone’s understanding as you work on a problem. ill-structured a “wicked” problem that has multiple possible solutions. As we began connecting electronic goodies to one another, we realized neither of us had used a solder less breadboard for. They are supposed to make it easy to connect components without soldering, and I could see that it would be easy to insert leads or wires into the board, but how would one make connections between components? A quick Google search gives the answer. I've pasted the basic diagram above too as a reference for later, when I forget.

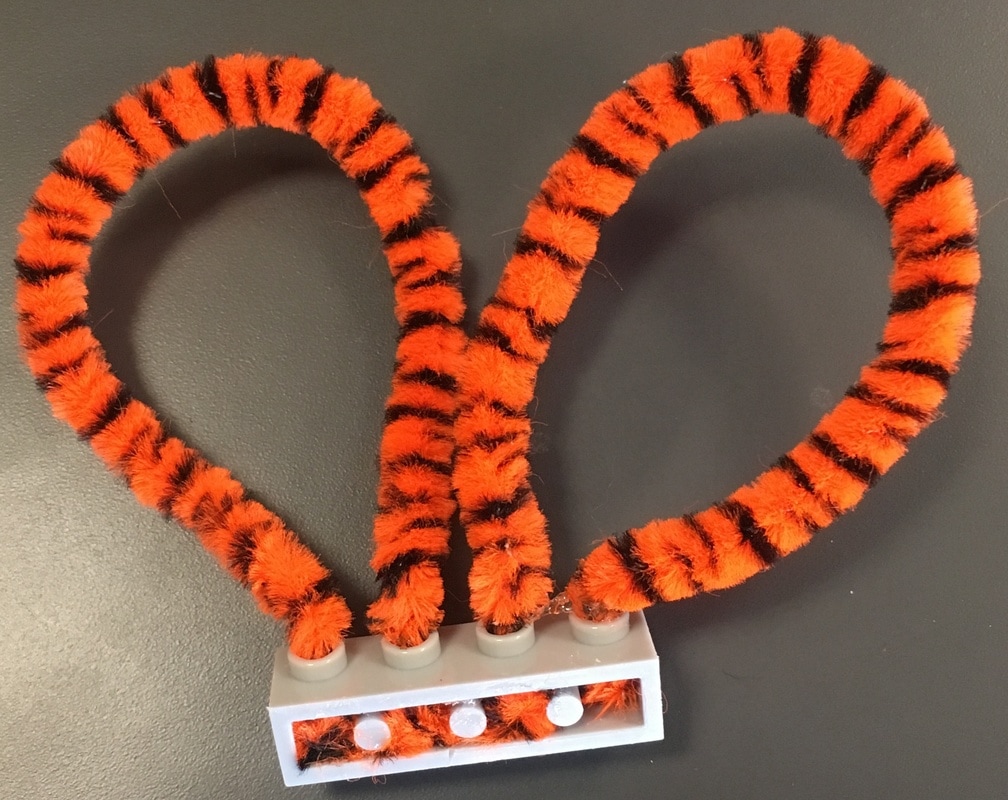

We have been holding a series of open studios, which have been fun and something I look forward to, but yesterday was the best one so far. We had an interesting range of people show up, and we tried out our flying fish camera, which gets ~two full tables, and whatever you do over them, but not much else. One issue that emerged was that we had too much stuff, too many options. I knew I had clear goals (trouble shoot my cardboard LED sculpture and coerce LEGOs). But probably no one else did. But I did not want to do something structured. This was supposed to be OPEN studio. One affordance of having 8 people crowded around these two tables and a pile of stuff (the two tables, again, dictated by the flying fish cam), was that it was easy to do just in time (or maybe slightly late) instruction. Someone was sewing with conductive thread, and it was easy for me to lean over, hand off a little LED and battery, and demonstrate how to test an LED if you are unsure about the current direction. And that led to a successful and interesting etextile product. It was a nice mashup of sewing skill combined with circuitry. The classic "you got your peanut butter in my chocolate" part of maker culture that I first fell in love with. The table got messier by the end of the hour! I thnk Previously, I'd been trying to hide anything that seemed like instructions for how to do something. I forgot to this time, and of course someone found them and followed them. I noticed that they dove right in—maybe into a space that they would not otherwise have felt comfortable. I admit to being pretty anti-kit in general. Except, of course, when I am not. For instance, the other day a new piece of furniture I'd ordered for the lab arrived. Well, technically, about 200 pieces (including screws) arrived in a slender box. And I admit to being pretty proud that I forged in and assembled this new piece of furniture for our lab. And it was intimidating EVEN with instructions. So I ended up with a nice piece of furniture, and maybe feel more confident about assembling. But I don't certainly don't think I learned anything about how to MAKE a piece of furniture. Though perhaps this would be different if I had the right scaffolds. Suppositional points along the way that get us to think, what else could this be? See that thing you just did? What else could you do with that technique? I think this gets right at the heart of what I am trying to do with this space actually—identify strategies that we can use deliberately to surmount barriers, overcome intimidations, and break out of the mundane. I am determined to see what other things we can coerce LEGOs to do. Chris showed me a few new tricks, but I was most proud of this discovery: a weird brick with openings on the side—exactly the kind that I never know what to do with—is PERFECT for threading things through, such as tiger striped pipe cleaners! Which become wonderful ears!  And I did finally get my little LED sculpture working. I think the copper tape maybe is not as conductive on its sticky side, plus I think 3 LEDs might be the limit on one little battery. I want to submit an abstract to 4S related to other work I do, and I stumbled on a call for abstracts that I am trying to fit my work in the OILS Learning Lab into: 64. Craft as Practises of Knowledge Making I love it, but I find it a bit jargon-laden for my taste. I have been working on a lab lexicon that aims to give everyone in the room ownership of the research constructs in play. I want the work to be smart, open and accessible, not sound smart and be closed because it is inaccessible. And so I am trying to place my ideas in a voice that will sound academic yet accessible. I want to talk about how our data collection tools (ourselves, various recording devices) support investigation into and reflection on creative process, and how these could be a means to share or further remix. So far, I have recorded myself gluing muppet fur to LEGO blocks, and an initial e-textiles experiment with eye-tracking. The biggest take-aways from eye tracking so far are (1) plug in your computer as I used half my battery in less than 20 minutes; (2) have some external storage handy, as 18 minutes of eye-tracking gave me over 6 GB of data, and (3) I am not a touch typist. Ok, so I already knew that last one. In school, I refused to take keyboarding/typing because it was advertised as a guaranteed job...as a secretary. I was NOT going to be a secretary, so I simply refused to learn. Still, I see a lot of potential in these recording tools, from a head-mounted GoPro to the eye tracking systems, to reveal more about our processes, our attentions. I felt a heightened sense of awareness while wearing the eye tracking in particular. I have spent a lot of time in front of cameras as part of data collection, and as a result, they melt into the background for me. But this was different.

For example, I decided to search online for sample code to explore Lilypad Arduino. So I typed in "Lilipad Arduino code." And I got several results of COUPON codes. Yay! And then I looked away quickly, not wanting the cameras to record my off-task behavior. It remains to be seen if the eye tracking leads us somewhere with analyzing point of view that the GoPros cannot. In their favor, eye tracking is way more comfortable to wear if you are just sitting at a table! |

VanessaDesigner and researcher, researching designing. Archives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed