|

Imagine you have a brick, a string, a paperclip, and chewing gum. Come up with as many possible uses of them as you can.

Does doing problems like this make you more creative? While you can get better at tasks like this—tasks that are context light or context free—such tasks don't appear (from the research literature) to enhance creative capacity in disciplinary/domain-specific settings. Creativity seems to be discipline-specific. And this makes sense. Many people feel their creativity is welcomed in certain places (creative writing, art class) and unwelcome in others (math class?). But this also varies across people, mostly based on the experiences they have had. Some people feel very creative in mathematics yet feel rigid and constrained in prototypically creative spaces. So one of the things we are exploring is how to reframe this problem. If giving people creativity tasks is not the answer, perhaps the problem is not with the tasks themselves, as much as the instructional design surrounding the tasks. Or perhaps we need a continuum of tasks, stepping people from tasks that invite their creativity to those that repel it. I suspect we need some practices as well, some scaffolds to fade. So the questions I have are: How might we design learning experiences so that learners get more reflective/metacognitive about the strategies they use to be (un)successfully creative, and the conditions that (dis)invite their creativity? How can we foster a willingness to approach problems/situations as malleable/reframable? What practices/tools could help in this endeavor? I think the construct I want to develop is framing agency—that is, the ability to take ownership of problems/situations and shape them, flip them, find their tractable parts, their movable parts, and rework them into something better. Framing agency is something I have and use daily. Having spent some time in situations where I wasn't comfortable being my weird, creative, nerdy, playful self, I am keenly aware how context-dependent agency is. Having suppressed that part of myself for the better part of 5 years, and then having come back to myself, I feel like I have good grounds for comparison. I am happier and do more interesting, more fulfilling work when I have it.

0 Comments

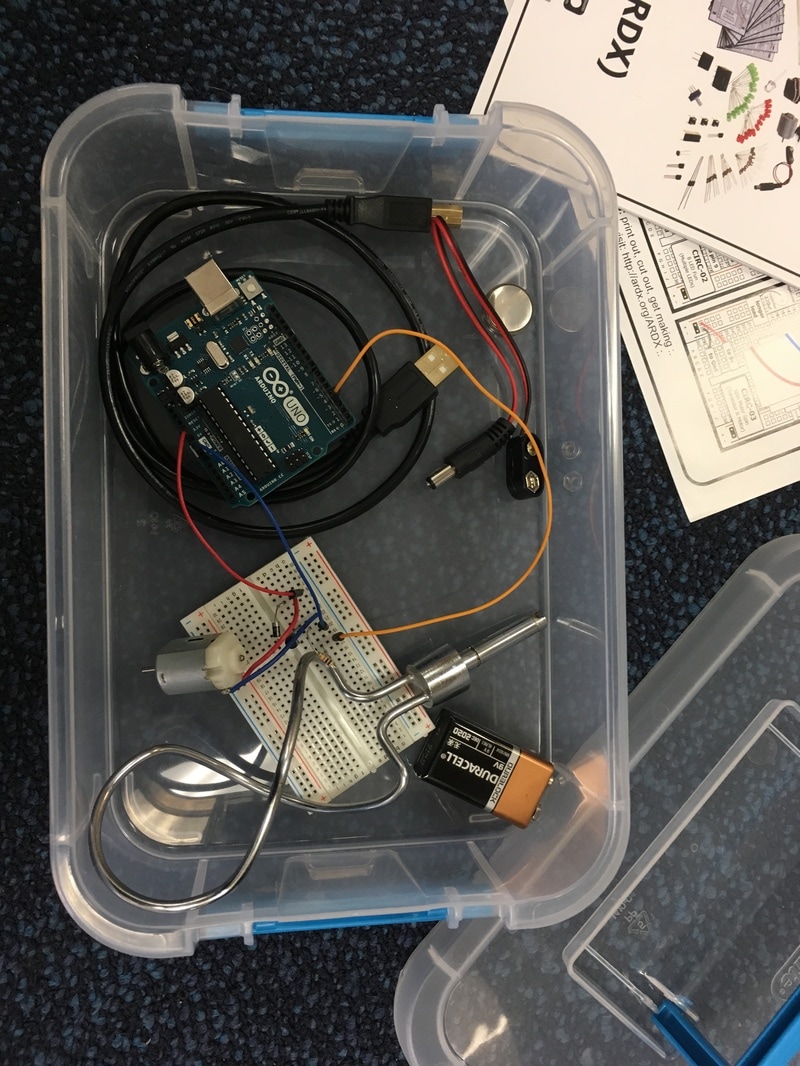

I named this blog 'making space,' which was a rapidly-made decision that turned out to be productive. It felt like it fit at the time. But I didn't know why. Most spaces where people make things are called "maker spaces" (or fablabs). And that says that you have an identity as a maker. I don't always feel like a maker, and maybe you don't always feel like a maker, but that doesn't stop us from making things. And we are also making the space into something new. When giving a tour of the space the other day, someone commented on our column, which began as an eyesore—a bug—that we have now transformed into the coolest part of the space—a feature. So it is a space for making and a space we are making. As a constructionist, (this stance is tied to why I decided to blog about all this, to position it as public), I also see it as a space for making ideas, constructs, studies, etc. Which makes me ponder, in this exploratory time, what are we making progress on? In reflecting on this with Richard Reeve, I found something exciting in the making: We are developing a practice—not yet formalized—that could be very helpful for eliciting problem framing. One of the big challenges in studying problem framing is deciding what is sufficient evidence, in terms of whether framing is happening, what the frame is, and when it has changed. Something I have noticed in my own exploratory work is that I began using a sort of think aloud protocol to narrate my work. In doing so, I realized I was making clear my long term problem goals (the larger problem frame), as well as the short term and emergent goals. I have been trying to turn a beater from a stand mixer into PKE meter. And I know I need to learn some programming and some electronics, both of which are (mostly) new to me. A future PKE meter! So this tells me I can attend to two frames at once, and I don't think we talk much about this in the study of problem framing. But it also means we have a practice we can build into our studies, a practice we can scaffold with technology, or with instruction. It is not exactly goal-setting, though it resembles it. (And Michelle Jordan's work on managing uncertainty seems pretty relevant here). It is attending to—and giving voice to—these emergently, in conversation with materials, as reflective practice. Of course, there are many literatures to build on here: metacognition, self & co-regulation, probably others... But so much of those have focused on well-structured problem solving, that I don't know how well they fit, whole-cloth. What I am after here is enhancing peoples' capacities to take ownership of problems, to frame and reframe them, to learn with excitement, and to forge ahead in the face of uncertainty by using resources, tinkering, and generally failing a lot. Using resources and tinkering, right before failing a lot!

One of the things I want to do is avoid what I (provocatively) refer to as "sweatshop theory." I don't think it serves us well to do work that is not accessible to people, but is built on the backs of people. In chatting with my colleague, he mentioned that he writes for reviewers. That seems like a very prudent strategy. But it is not mine. I realized I write for my participants. When I write, I imagine them reading it. This is probably common for those who have done lots of participant observation and member checking, but I don't think I had articulated it until recently. And so, in this vein, I want to start building a lab lexicon that makes the terms I am exploring accessible. Here is a start: materiality how the materials “talk back” to you as you work with them. What do these puffballs tell you to do? (re)framing

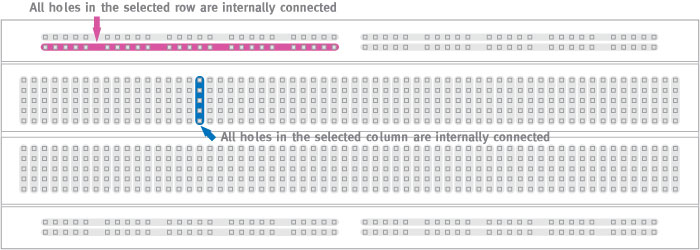

how you decide what parts of a problem matter and what parts you will work on. fixation getting stuck on an idea or an assumption about how something “ought to be.” co-regulate how you plan, monitor, and evaluate everyone’s understanding as you work on a problem. ill-structured a “wicked” problem that has multiple possible solutions. As we began connecting electronic goodies to one another, we realized neither of us had used a solder less breadboard for. They are supposed to make it easy to connect components without soldering, and I could see that it would be easy to insert leads or wires into the board, but how would one make connections between components? A quick Google search gives the answer. I've pasted the basic diagram above too as a reference for later, when I forget.

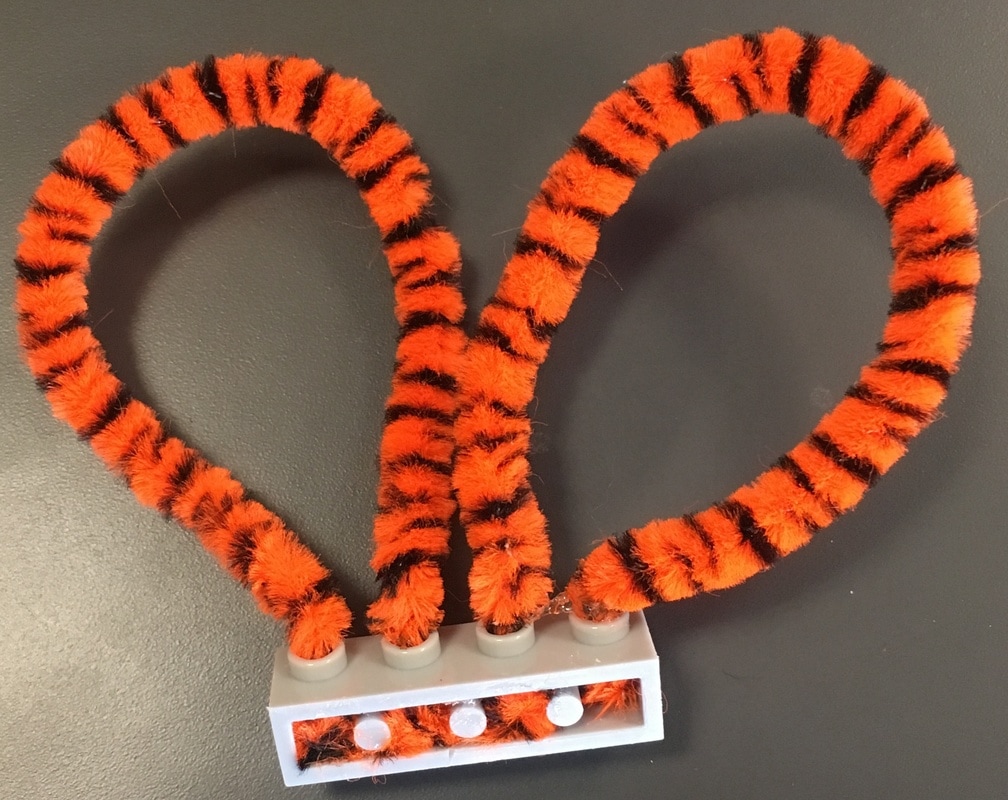

We have been holding a series of open studios, which have been fun and something I look forward to, but yesterday was the best one so far. We had an interesting range of people show up, and we tried out our flying fish camera, which gets ~two full tables, and whatever you do over them, but not much else. One issue that emerged was that we had too much stuff, too many options. I knew I had clear goals (trouble shoot my cardboard LED sculpture and coerce LEGOs). But probably no one else did. But I did not want to do something structured. This was supposed to be OPEN studio. One affordance of having 8 people crowded around these two tables and a pile of stuff (the two tables, again, dictated by the flying fish cam), was that it was easy to do just in time (or maybe slightly late) instruction. Someone was sewing with conductive thread, and it was easy for me to lean over, hand off a little LED and battery, and demonstrate how to test an LED if you are unsure about the current direction. And that led to a successful and interesting etextile product. It was a nice mashup of sewing skill combined with circuitry. The classic "you got your peanut butter in my chocolate" part of maker culture that I first fell in love with. The table got messier by the end of the hour! I thnk Previously, I'd been trying to hide anything that seemed like instructions for how to do something. I forgot to this time, and of course someone found them and followed them. I noticed that they dove right in—maybe into a space that they would not otherwise have felt comfortable. I admit to being pretty anti-kit in general. Except, of course, when I am not. For instance, the other day a new piece of furniture I'd ordered for the lab arrived. Well, technically, about 200 pieces (including screws) arrived in a slender box. And I admit to being pretty proud that I forged in and assembled this new piece of furniture for our lab. And it was intimidating EVEN with instructions. So I ended up with a nice piece of furniture, and maybe feel more confident about assembling. But I don't certainly don't think I learned anything about how to MAKE a piece of furniture. Though perhaps this would be different if I had the right scaffolds. Suppositional points along the way that get us to think, what else could this be? See that thing you just did? What else could you do with that technique? I think this gets right at the heart of what I am trying to do with this space actually—identify strategies that we can use deliberately to surmount barriers, overcome intimidations, and break out of the mundane. I am determined to see what other things we can coerce LEGOs to do. Chris showed me a few new tricks, but I was most proud of this discovery: a weird brick with openings on the side—exactly the kind that I never know what to do with—is PERFECT for threading things through, such as tiger striped pipe cleaners! Which become wonderful ears!  And I did finally get my little LED sculpture working. I think the copper tape maybe is not as conductive on its sticky side, plus I think 3 LEDs might be the limit on one little battery. |

VanessaDesigner and researcher, researching designing. Archives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed